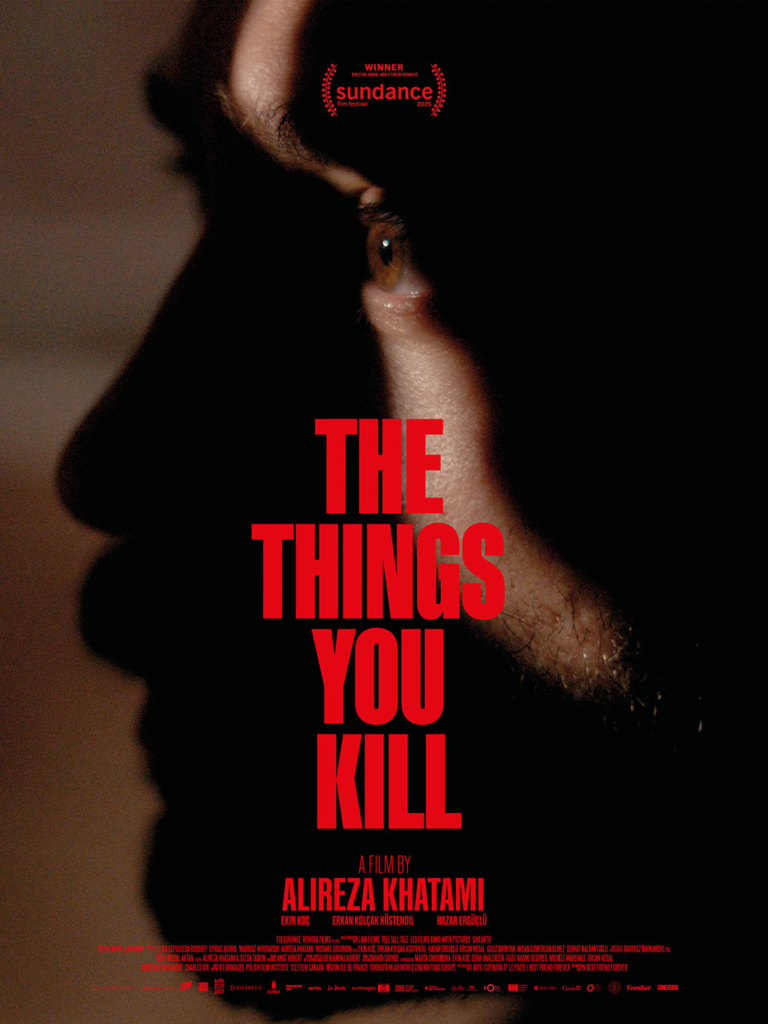

The Things You Kill — A Q&A with Filmmaker Alireza Khatami

What initially inspired you to make this film? Was there a particular image, dream, or event that sparked the idea?

The spark was personal. I was wrestling with an old family wound and a cycle of violence I could not ignore. About seventy percent of the film draws from things that happened to me or my family. It took eight years to turn that kernel into cinema. The first scene begins with a dream because the project began with questions that would not let go. I often say a story worth telling should scare you. This one did. It became a requiem for a man inside patriarchy, and a study of how violence moves from father to son.

Your film has strong David Lynch influences. What aspects of his work inspired you most, and how did you adapt them to a Turkish setting?

I admire Lynch for revealing the uncanny inside the everyday. That gave me permission to blur reality and dream without imitating his images. I grounded the strangeness in concrete university corridors, omnipresent flags, portraits of authority, cold empty apartments, and wide open fields. For me, the nightmare often sits on the surface, so tension and unrest grow naturally from social reality. The mood may feel Lynchian because I embrace the dark shadows.

Did any specific Lynch films influence your approach? Or was it more the overall mood and method?

It was the method. I was following an ethos that trusts the unconscious while filtering it through my storytelling. If I have to mention a movie then it would be Lost Highway that showed me a story that can pivot midstream and still make emotional sense.

What psychological themes or mental states does the film explore, and how are they reflected in the visuals and sound design?

Guilt, paranoia, and inherited trauma shape Ali’s mind. I used mirrors, shadows, frames within frames, and shifts in focus so the audience doesn’t think about these themes but feels them viscerally. Instead of a score, I used silence and heightened everyday sounds at key moments so the audience sits inside his nerves. As his psyche fractures, the image loosens, and the soundscape hollows out.

How does your film blur the lines between reality, memory, and dream, and why is that important to the story?

The film questions the stories we cling to. Horror isn’t a monster, it’s your own reflection, the image you accept without question until the narrative cracks. I stage events in plain sight, then slowly invite the audience to doubt what they saw. That ambiguity resists easy hero–villain logic and demands a careful reconsideration. Certainty can be dangerous. By unsettling the ground under Ali’s feet, we test our own appetite for revenge and our responsibility to the truth. Do we really want to know?

Is your story a metaphor for a deeper societal or cultural tension in modern Turkey?

It’s a story of a family under patriarchy that becomes a mirror of a nation led by symbolic fathers. Is that Turkey alone? I don’t think so. Private silence and public authority feed the same cycle of violence everywhere. The film’s imagery of flags and portraits amplifies that link. The questions are intimate and political at once, and not confined by borders.

What were the biggest creative and technical challenges of directing a psychological thriller with surreal elements?

Balance. I wanted bold form anchored in believable behavior. Censorship forced us from Iran to Turkey late in prep, then we rebuilt in a new language with limited resources. We solved problems through precision and restraint. Every shot had to earn its place. The goal was calibrated ambiguity, not confusion, to create an unsettling space for self reflection.

Can you describe your approach to cinematography, especially in creating a disorienting or dreamlike atmosphere?

We moved between claustrophobia and vastness. The camera often observed from a distance, framing through doors and windows to layer reality. Interiors were muted and boxed; countryside scenes were bright and spacious yet uncanny, as if openness exposed him even more. Long, controlled moves and generous negative space kept the viewer slightly off balance. I gave Ali a locked, controlled camera and Reza a handheld, fluid one. As the story moves toward its final act, Ali gradually earns that fluidity, the camera becomes freer, able to stay still or move.

How did your editing process influence the final structure and tone of the film?

We built a slow burn, a rupture, and an unvarnished aftermath. Early cuts are classical to lull you, until the midpoint turns the film on its axis. We strip away music and explanation so images carry the weight. Every cut was made to preserve the dread and give it the space it needed.

How does Turkish culture, history, or folklore inform the mood and symbolism of the film?

Atatürk’s presence and national iconography echo the father theme. Family dynamics reflect real social codes, including quiet resistance. The film borrows the region’s rich poetry background as inspiration, where metaphor touches daily life. Turkey’s East-West tension threads through Ali’s struggle for finding his place in the world.

Do you want the audience to understand the film literally, or emotionally?

Emotionally. The plot is a vessel for the questions. I would rather you feel the truth in your bones than map every beat on a flowchart. If the film lingers and pushes you to reflect on violence and complicity, it has done its work.

What do you hope people search for or talk about after seeing your film?

I hope they talk about the stories they’ve invented to keep their lives together. I hope they talk about what it means to hold a life together, and how to navigate this existence that’s been given to us without a user manual.

Can you walk us through one key scene, from concept to final cut, that best represents the film’s psychological and visual language?

The confession scene is the core. I wrote it after confronting my own buried feelings, ones I had never shared with anyone. Ekin Koç, our lead actor, was nervous about it, and I had no clear plan for how to shoot it. I also refused to tell him how to play it. On the day of the shoot, we began with a tight medium shot. I was watching Ekin on the monitor as he tried to find his place for the camera. For a moment, he slipped out of focus, and I loved seeing his eyes blur. There was a distance, but a profound intimacy too. I decided then to film the entire scene out of focus. It terrified my producers and crew, but we went through with it. Ekin delivered a calm, almost detached confession that became the boldest and most truthful choice for the moment. The camera and the performer became one. It holds raw emotion and formal risk in the same frame. It remains the most difficult scene I’ve ever shot.

How did you work with your actors to create performances that feel real, even within an unreal world?

For me casting began with emotional truth. We built private backstories and a safe set so risk felt possible. I gave simple, internal prompts and welcomed restraint over theatrics. When the style bends reality, sincerity keeps the audience tethered. The actors carried that honesty.

What advice would you give to filmmakers who want to explore surrealism or psychological horror in their own cultural context?

Start from what truly unsettles you. Let local symbols, language, and folklore come organically. Don’t force it. Learn the grammar, then bend it with purpose. Trust your audience, protect clarity of feeling, and use limitations as fuel. Be bold and compassionate at the same time. But above all, tell a story that scares you.

Which filmmakers do you see as spiritual or creative influences beyond David Lynch?

Kiarostami for poetic realism and patience. Kurosawa for moral clarity and visual precision. Buñuel for subversion, Bergman for the psyche, a touch of Tarkovsky for memory and time, and Ildikó Enyedi for her lyrical sense of wonder. Lee Chang-dong for his deep philosophical reading of the world. The list can go on!

Do you think there’s a growing movement of psychological or surreal cinema in Turkey?

I see the seeds. Many filmmakers are testing genre to speak about hard realities. Audiences are more open, and metaphor often travels further than literal critique. It feels like an emerging chorus rather than a single voice.

If someone Googled your film five years from now, what would you want the headline to say?

Five years from now, I love this question. The film was meant to hold a mirror to certain truths. So I’d want that to shine through. Perhaps: “The Things You Kill continues to haunt the audience five years later.” If I see a headline along those lines in five years, I’ll know that the film lived on in the minds and hearts of its audience. That would be the best reward of all.

FOLLOW US